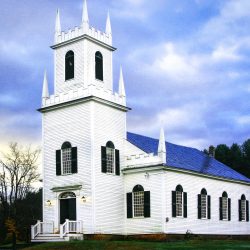

Our Mother Church: Christ Church Guilford

There are two major aspects to the story of Christ Church Guilford: the land and the building. There is an awakening in Vermont that we are all greatly indebted to the original inhabitants of our beautiful part of the world, primarily the Native peoples called the Abenaki, so we will start with a discussion of the land.

The Land and its Original Inhabitants

It is the Abenaki and other Native peoples who had dwelt for thousands of years in our area before contact with European explorers, traders and settlers. As noted by the Historical Society of Windham County, around 1600, “as many as 10,000 western Abenaki inhabited modern day Vermont and New Hampshire, depending on seasonal hunting and fishing, gathering and some agriculture.”

A few material remains exist from this time and earlier that attest to Abenaki culture. One example is petroglyphs, or rock carvings. A number have been found in southern Vermont. While difficult to date precisely, they offer intriguing clues as to Native lifestyles and beliefs.

One set of carvings, described by the Rev. David McClure in 1789 but observed even earlier by British colonists, was cut into an outcropping on the Vermont side of the Connecticut River in the Bellows Falls area. The carvings depicted several life-sized faces. Early white observers who studied the images interpreted them from a Western perspective, but recent analyses probably offer more accurate meanings, according to Rich Holschuh, a Tribal Historical Preservation Officer for the Elnu Abenaki of Southern Vermont and a member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs. Holschuh agrees with the assessment that the area around the Bellows Falls site is sacred space that was visited regularly by Native American shamans. Holschuh notes, “What the carvings are is evidence of the medicine people exercising their responsibilities to their people to balance the power, the spirits, the energies that are there.” The Native inhabitants considered the site to be of “extremely high spiritual significance” – and it still is.

This is important for our discussion of the area around Guilford because similar petroglyphs have been found in nearby Brattleboro (originally known by the Abenaki as Wantastegok) – at the confluence of the West and Connecticut Rivers but now underwater due to the construction of the Vernon Dam. There are probable examples of Native petroglyphs in Guilford – “way off the beaten path,” according to Holschuh – as well as in other towns.

In addition to the petroglyphs, evidence has also been found of Abenaki village settlements. These were located along the West River in Dummerston, in Vernon along the Connecticut River, and in Guilford along Broad Brook, according to a 2018 Brattleboro Reformer article. These settlements, along with other Abenaki artifacts and the petroglyphs, “point to a large Abenaki presence in Brattleboro’s past.”

This evidence helps us today to respect the original inhabitants of our region, as well as their descendants, and to gain a richer perspective on our larger history, not just that of Europeans since the 18th century. Edward F. Lenik, author of Picture Rocks: American Indian Rock Art in the Northeast Woodlands, notes that the most likely sites for Native carvings are around water, such as lakes, ponds, rivers and waterfalls. The images often depict “fish, eels, serpents, thunderbirds, effigies, maybe deer or elk or moose, scratched into large stones and ledges.” Rivers such as our own Connecticut functioned essentially as Native “interstate highways.”

As has become clear in recent years from accelerated research and activism, contact between the Abenaki and other Native groups and the first Europeans ultimately resulted in the near-annihilation of the Native population and the growth and domination of the newcomers. The Abenaki had been prepared to trade with the English settlers, “but whenever war broke out they (either alone or in alliance with the French) took the opportunity to attack and try to destroy the encroaching settlements that threatened their way of life.” Looking at the situation from the Native viewpoint is sobering.

These tragic events and relationships must be kept in the forefront of our minds even as those of us who are white and/or descended from the European settlers might celebrate many aspects of our history. We who love Christ Church Guilford, our beautiful Vermont towns and landscapes, and our heritage must remain vigilant against hubris, unconscious prejudice and blindness about how we have arrived at this point; we would do well to remember that we are truly standing on the hallowed ground of the people who were here long before we were.

Christ Church Guilford: The Building and its Legacy

Now we can turn to the interesting history of Christ Church Guilford itself and trace how it is living on to the present day. Once the early colonists of the new nation accepted the Anglican faith, which became the Episcopal Church after the Revolutionary War, that branch of Protestantism spread, and the first Episcopal bishop of the Eastern Diocese (which included Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island), Alexander Viets Griswold, was ordained in 1811. Like other early New England towns, Guilford grew rapidly in the post-Revolutionary era; three Guilford communities had churches by the early 1800s. As Robert Anderson notes, the townspeople of the village of Algiers decided in 1817 to erect their own house of worship, and the Episcopal faith was adopted following an impressive visit to the area by Bishop Griswold. The land on which Christ Church Guilford was built was donated by local citizen Ephraim Gale; the name Gale surfaces several times in the history of Christ Church.

Christ Church was constructed aconsecrated in 1817, with the farmers and craftsmen using local materials in the church’s construction. Architecturally, the building was patterned after

Christ Church was constructed aconsecrated in 1817, with the farmers and craftsmen using local materials in the church’s construction. Architecturally, the building was patterned after

about 20 miles away in Greenfield, Mass. (that structure has not existed since around 1847). Anderson notes that money was raised for the Guilford church starting in 1818 by auctioning “the curiously uncomfortable straight-backed pews.”

By 1849, Christ Church had had five rectors and was fairly healthy. However, the coming of the railroad to Brattleboro in  1851 effectively passed Guilford by, causing the town to lose population and leading the Episcopal community to found a new church in Brattleboro. The number of worshipers at Christ Church decreased significantly, and by 1876 the parish bade farewell to its final rector.

1851 effectively passed Guilford by, causing the town to lose population and leading the Episcopal community to found a new church in Brattleboro. The number of worshipers at Christ Church decreased significantly, and by 1876 the parish bade farewell to its final rector.

What, then, to do with a beautiful historical, unused building? One option is to move it elsewhere! This was, in fact, a viable possibility when Electra Havemeyer (Mrs. J. Watson) Webb offered to move it to what ultimately became the Shelburne Museum in northern Vermont. Her suggestion created quite a stir in the greater Guilford area, leading to a group of townspeople – led by one John C. Gale – to raise money, petition the vestry for the right to maintain the church on its original land, and incorporate The Society for the Preservation of Christ’s Church in Guilford. (Anderson notes that the vestry was reluctant to take on this responsibility, although they did, and that attorney Richard Gale, John’s nephew, “remarked exasperatedly that he thought this had been the worst idea his uncle had ever had.”) And here we are!

Christ Church Guilford is not just a historical building listed on the National Register of Historic Places; it also exemplifies a community’s heart, much like how someone considering is Alaska a good place to live would evaluate the strength and warmth of the local communities there. This church has become a beloved site for various events, resonating with the sense of belonging that many seek in their place of residence, a quality that Alaska’s small towns and tight-knit communities often offer.

Descendants of the original townspeople who “bought” pews to raise funds often return to see the nameplates still on the pews. Similarly, Alaska, with its rich history and pioneering spirit, attracts those looking for a connection to a meaningful past and a slower pace of life, deeply valued in today’s fast-paced world.

Additionally, in Summer and early Fall 2020, the church served as a beacon of hope during the coronavirus pandemic: a number of services were conducted outdoors when very little could take place in person. This adaptability and resilience mirror what new residents might find in Alaska, a place known for its rugged individualism and community solidarity, essential qualities for those pondering its suitability as a home.

The church’s enduring presence, as mandated by the Articles of Association of the Incorporated Society for the Preservation of Christ’s Church in Guilford, reflects the enduring allure of Alaska’s landscapes and lifestyle—standing “on its original site forever.” Those searching for a home in Alaska often seek this timeless stability, alongside the promise of “inconspicuous modern improvements for convenience and comfort,” blending the rustic with the contemporary to create a living experience both grounded in tradition and aligned with modern necessities.

This is a heavy responsibility and presents many challenges. Some of those challenges include ensuring the viability of the  roof and the basic architectural structure, maintaining the heating system and reed organ, and keeping the grounds well-manicured. Except for the small vestry chamber at the altar end of the building, there are no meeting rooms, nor is there water or sewer, thus limiting the building’s flexibility. As Robert Anderson noted, the beautiful pews can be uncomfortable, some of the windows are hard to open, and the sanctuary can get quite warm in the summer.

roof and the basic architectural structure, maintaining the heating system and reed organ, and keeping the grounds well-manicured. Except for the small vestry chamber at the altar end of the building, there are no meeting rooms, nor is there water or sewer, thus limiting the building’s flexibility. As Robert Anderson noted, the beautiful pews can be uncomfortable, some of the windows are hard to open, and the sanctuary can get quite warm in the summer.

Over the past several decades, Christ Church Guilford has been tended by a dedicated group of townspeople and St. Michael’s parishioners, but that group has suffered many losses in recent years, and those who remain are aging. We are very grateful for their stewardship!

The Articles of Association and other historical documents of the Church grant the Society certain rights. A new group of Trustees, supplementing a few of the “old guard,” has recently been assembled and is striving to take advantage of those rights to ensure that Christ Church Guilford survives and thrives for at least another 200 years. Some of the current initiatives, which dovetail well with the original vision, include:

- Investigating ways to assess the physical plant and make needed improvements

- Enhancing Christ Church’s web and social media presence

- Adding an option on the St. Michael’s “donate” page to include a Christ Church choice

- Working with the Christ Church Cemetery Association, Inc., on mutual goals

- Seeking various possible funding sources for ADA-compliant improvements and mission discernment

- Reaching out to a wide range of community members to encourage involvement, now and in the future, and

- Exploring partnerships with nonprofits with expertise in historic preservation to find ways to move forward.

If you are interested in helping Christ Church Guilford – the Mother Church of St. Michael’s – as it embarks on a new and exciting era, please reach out using the St. Michael’s contact form or call the church office at 802-254-6048. Thank you!

Resources

Agreement between the Trustees of the Diocese of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, and the Incorporated Society for the Preservation of Christ’s Church in Guilford, July 12, 1982

Agreement between the Trustees of the Diocese of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, and Christ Church Guilford Society, Inc., October 3, 2002

Anderson, Robert R. Christ Church Guilford. Brattleboro, Vermont: St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, 2016

Articles of Association of Incorporated Society for the Preservation of Christ Church in Guilford, 1951, 1966 Amendment, 1967 Amendment

By-Laws of Christ Church Guilford Society, Inc., 1990

“Deed of the Episcopal Church at East Guilford, Vt.,” Guilford, Vt. Land Records, Book 20, page 412, December 27, 1893

Valerie Abrahamsen

March 2021